More articles Friday 23 August 2019 7:30pm

Turkish writer Elif Shafak: “Populism is a fake answer to real problems”

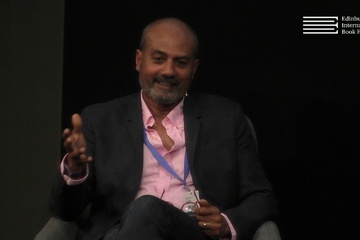

“Now we know that no countries are immune to toxic populism or toxic nationalism, in fact we’re all in the same boat together,” said Turkish author and human rights activist, Elif Shafak in an emotional discussion about the rise of populism, nationalism and identity politics with BBC special correspondent and Chair of the Edinburgh International Book Festival, Allan Little.

The pair discussed the illusion of safety that so-called “solid countries” in the western world like the United States had for “liquid countries” like Turkey around matters of social and political equality.

“If you go back to the 1990s and early 2000s, you will remember there was so much optimism in the world. Back then people thought, ‘ok, facism had been defeated, communism had lost and liberal democracy seemed to be the only triumphant power or ideology’. So people thought that history, from that moment onwards could only go forward in a linear way and so that comfort made them think that the countries that were lagging behind would sooner or later catch up with the rest of the world.

“So human rights, freedom of speech, women’s rights, minority rights, those were struggles that needed to be upheld in those liquid countries, those backward countries, but the western world was regarded as safe, solid and steady and you really didn’t have to worry in the west about democracy anymore because it was already achieved. That threshold had been passed, and I think what has changed after the year 2016 was that dualistic way of reading the world.”

Discussion turned to the topic of Shafak’s motherland of Turkey, a place she gained notoriety for daring to write books that worked against the grain of nationalism that has been deeply entrenched in the country. One book, The Bastard of Istanbul, which looked at a family living in the aftermath of the Turkish genocide of Armenians, almost resulted in Shafak facing a potential three-year jail term.

“Usually Article 301 has been used against journalists, scholars, historians,” said Shafak, “but this was the first time it was used against a work of fiction. The words of the fictional characters have been taken out of the book by ultra-nationalist groups and then used as evidence in the courtroom to prove that I was insulting Turkishness. In the end, my Turkish lawyer had to defend my Armenian fictional characters in the courtroom. Afterwards, we were all acquitted, me and the fictional characters, but still I had to live with a bodyguard for about a year and a half.”

For Shafak, the topic of nationalism or tribalism is something she is wary of. She feels that what ties her to her fellow people is not her nationality, but more so the struggles and experiences they have shared. This view of plurality of identity is something she subscribes to but is afraid that once again we are reverting back to tribalism and linear identity instead of multiplicity and a feeling of belonging to different sections of society.

“My fear today, when I look at progressiveness, is that we’ve forgotten that emphasis on multiplicity and we are retreating more and more into our own tribes. That is something that scares me. I don’t think the answer to one kind of tribalism is forming another form of tribalism of our own. I think we all need to go beyond all echo chambers.

“I think there’s a reason why all populist demagogues love to divide. They love it when societies are divided into ‘us’ versus ‘them’. They thrive upon that. So if I retreat into a description of ‘us’ opposing a ‘them’, that only strengthens the hands of populist demagogues. So I think we need to find a way to go beyond this duality of ‘us’ versus ‘them’.”

Another thing that troubles Shafak is that the overloading of information we experience today is leading to apathy and desensitisation, which she believes is one of the most dangerous emotions, or lack thereof, that we can feel. The memoirs of people who have survived the darkest moments of human history, like the Holocaust, ask ‘how could this have happened? and by reading them Shafak has come to the conclusion that these events may not have been driven by powerful, hard emotions, but by desensitivity.

“They’re saying maybe the opposite of goodness is not necessarily badness. Maybe the opposite of kindness is not necessarily badness. So they’re saying the opposite of goodness is numbness. It’s the moment we become numb or indifferent, you know, we stop feeling or questioning or asking questions.”

Look, Listen & Read

- 2026 Festival:

- 15-30 August

Latest News

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections