More articles Tuesday 21 August 2018 7:00pm

Muriel Spark is Still Scotland’s Greatest Living Writer, says Ali Smith at the Book Festival

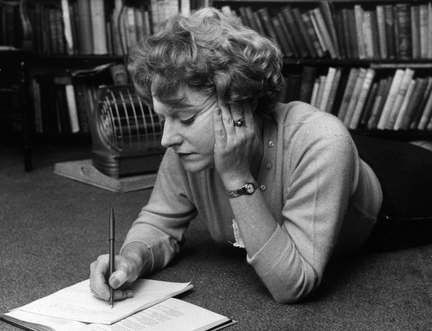

Ali Smith doesn’t like being referred to as 'Scotland’s greatest living writer', but the description seems to have stuck at this year’s Book Festival after Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s First Minister, used it during her interview with the author. Today, with a smile, Smith purposely applied the honorific to another author, Dame Muriel Spark—despite the novelist, short story writer, poet and essayist having died in 2006.

As Val McDermid explained, while 'chairing an event that doesn’t need chairing', the great thing about Muriel Spark 'is that her physical body may not be here any longer, but what we have is the body of her work, which is wonderful'.

Smith was once again delivering her essay on Spark, originally presented to the Muriel Spark Society in November 2017 and now published in book form. Muriel Spark’s continued relevance is a core theme: as an example, Smith turned to the 1965 novel, The Mandelbaum Gate, set in 1961 Jerusalem. 'Nothing in it was not relevant now,' Smith explained.

'The Mandelbaum Gate was what arose for Spark from a visit to the (Adolf) Eichmann Trial, which she made for a few days in 1961. She’d gone there to report on the trial for the Observer, but although she heavily annotated the transcripts she heard while she was there, she doesn’t seem to have submitted any reports to the Observer and, instead, we have this never-not-relevant novel. It’s not just about the past and the present that Spark concerns herself; she also concerns herself about the future.'

Many might say that the world has changed a lot since Spark’s death: not least the rise of social media platforms and the use of smartphones. 'Imagine Spark’s take on the iPhone,' Smith said. 'What would she have made of it? It would surely have involved the solipsistic ‘i” at the centre of it, the all-seeing all surveying ‘i’.

'Imagine her take on Twitter, a whole other kind of go-away bird. Imagine what she would have made of social media—the writer who knew how to puncture all the inflated importances and bloated-ness, who could hear the dog-whistle undercurrents, the emptinesses and manipulations of everyday social interaction.

'Even though she’s been gone a decade, even though we’re celebrating the centenary of her birth, her wisdom is the type that keeps on giving, and to think of Spark in the same room as recent technology’s new-found global powers – its attractions, its freedoms, its vagaries, its fascisms, and its seductions – is to know immediately that they’re just the same-old-same-old, the seductions of every form of language of all the centuries of the human choice between power play and poetry, between lies and truth. She’d have found the ghost in the machine, she just does every time; she does it so that we can too.'

Smith believes that Spark’s work will survive, ultimately, thanks to her 'lively inquisitions' of 'the fictions that we tell ourselves, the fictions politics tells its people, the fictions countries call their histories, the impetus to think, the revelations and manipulations of story, the hard-won lightness of the heart, hard-earned as her oeuvre matures.

'I can’t think of another novelist whose ever united the heart, the soul and the intellect with such interrogatory merriment as she has, or seen so clearly the 20th century and the spinner of industrial fictions it became, and seen our lives across that century with such fused lyricism, liberation, merciless understanding and forebearance.'

Look, Listen & Read

- 2026 Festival:

- 15-30 August

Latest News

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections

Major new partnership with Celtic Connections