The Saga of Ragnar Erikson

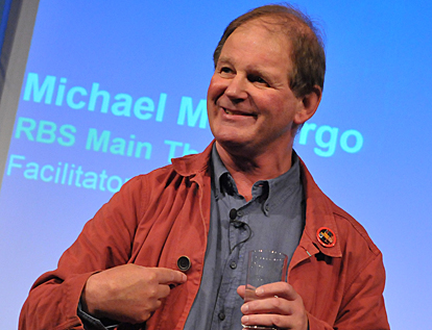

By Michael Morpurgo

We have commissioned a new piece of writing from fifty leading authors on the theme of 'Elsewhere' - read on for Michael Morpurgo's contribution.

14th July 1965.

As I sailed into Arnefjord this morning, I was looking all around me, marvelling at the towering mountains, at the still dark waters, at the welcoming escort of porpoises, at the chattering oyster-catchers, and I could not understand for the life of me why the Vikings ever left this land.

It was beautiful beyond belief. Why would you ever leave this paradise of a place, to face the heaving grey of the Norwegian Sea, and a voyage into the unknown, when you had all this outside your door?

The little village at the end of the fjord looked at first too good to be true – a cluster of clapboard houses gathered around the quay, most painted ox-blood red. On top of the hill beyond them stood a simple wooden church with an elegant pencil-sharp spire, and a well-tended graveyard, surrounded by a white picket fence. There seemed to be flowers on almost every grave. A stocky little Viking pony grazed the meadow below.

The fishing boat tied up at the quay had clearly seen better days. Now that I was closer, I noticed that the village too wasn’t as well kept as I had first thought. In places the paint was peeling off the houses. There were tiles missing from the rooftops, and a few of the windows were boarded up. It wasn’t abandoned, but the whole place looked tired, and sad somehow.

As I came in on the motor there was something about the village that began to make me feel uncomfortable. There was no one to be seen, not a soul. Only the horse. No smoke rose from the chimneys. There was no washing hanging out. No one was fishing from the shoreline, no children played in the street or around the houses.

I hailed the boat, hoping someone might be on board to tell me where I could tie up. There was no reply. So I tied up on the quay anyway and jumped out. I was looking for a café, somewhere I could get a drink, or even a hot meal. And I needed a shop too. I was low on water, and I had no beer left on board, and no coffee.

I found a place almost immediately that looked as if it might be the village stores. I peered through the window. Tables and chairs were set out. There was a bar to one side, and across the room I could see a small shop, the shelves stacked with tins. Things were looking up, I thought. But I couldn’t see anyone inside. I tried the door, and to my surprise it opened.

I’d never seen anything like it. This was shop, café, nightclub, post office, all in one. There was a Wurlitzer juke box in the corner, and then to one side, opposite the bar, the post office and shop. And there was a piano right next to the post office counter, with sheet music open on the top – Beethoven Sonatas.

I called out, but still no one emerged. So I went outside again and walked down the village street, up the hill towards the church, stopping on the way to stroke the horse. I asked him if he was alone here, but he clearly thought that this was a stupid question and wandered off, whisking his tail as he went.

The church door was open, so I went in and sat down, breathing in the peace of the place, and trying at the same time to suppress the thought that this might be some kind of ghost village. It was absurd, I knew it was, but I could feel the fear rising inside me.

That was when the bell rang loud, right above my head, from the spire. Twelve times. My heart pounded in my ears. As the last echoes died away I could hear the sound of a man coughing and muttering to himself. It seemed to come from high up in the gallery behind me. I turned.

We stood looking at one another, not speaking for some time. I had the impression he was as surprised to see me as I was to see him. He made his way down the stairs, and came slowly up the aisle towards me.

He had strange eyes this man, unusually light, like his hair. He might have been fifty or sixty, but weathered, like the village was.

“Looking at you,” he began, “I would say you might be English.”<

“You’d be right.” I told him.

“Thought so,” he said, nodding. Then he went on, “I ring the bell every day at noon. I always have. It’s to call them back. They will come one day. You will see, they will come.”

I didn’t like to ask who he was talking about. My first thought was that perhaps he was a little mad.

“You need some place to stay, young man? I have twelve houses you can choose from. You need to pray? I have a church. You need something to eat, something to drink? I have that too. Yes, you’re looking a little pale. I can tell you need a drink. Come.”

Outside the church he stopped to shake my hand and to introduce himself as Ragnar Erikson. As we walked down the hill he told me who lived in each of the houses we passed – a cousin here, an aunt there – and who grew the best vegetables in the village, and who was the best pianist. He spoke as if they were still there, and this was all very strange because it was quite obvious to me by now that no one at all was living in any of these houses. Then I saw he was leading me back to where I’d been before, into the bar-cum-post office-cum-village stores.

“You want some music on the Wurlitzer?” he asked me. “Help yourself, whatever you like, ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’, ‘Sloop John B’, ‘Rock Around the Clock’. You choose. It’s free, no coins needed.”

I chose ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’, while he went behind the bar and poured me a beer.

“I don’t get many people coming here these days,” he said, “and there’s only me living here now, so I don’t keep much in the bar or the shop. But I caught a small salmon today. We shall have that for supper, and a little schnapps. You will stay for supper, won’t you? You must forgive me – I talk a lot, to myself mostly, so when I have someone else to talk to, I make up for lost talking time. You’re the first person I’ve had in here for a month at least.”

I didn’t know what to say. Too much was contradictory and strange. I longed to ask him why the place looked so empty and if there were people really living in those houses. And who was he ringing the church bell for? Nothing made any sense. But I couldn’t bring myself to ask. Instead, I made polite conversation.

“You speak good English,” I told him.

“This is because Father and I, we went a lot to Shetland in the old days. So we had to speak English. We were always going over there.”

“In that fishing boat down by the quay?” I asked him.

“It is not a fishing boat,” he said. “It is a supply boat. I carry supplies to the villages up and down the fjords. There is no road, you see; everything has to come by boat, the post as well. So I am the postman too.”

After a couple of beers he took me outside and back down to the quayside to show me his boat. Once on board, I could see it was the kind of boat that no storm could sink. It was made not for speed but for endurance, built to bob up and down like a cork and just keep going. The boat suited the man, I thought. We stood together in the wheelhouse, and I knew he wanted to talk.

“My family,” he said, “we had two boats, this one and one other just the same. Father made one, I made the other. This is the old boat, my father’s boat. He made it with his own hands before I was born, and we took it over to Shetland, like the Vikings did before us. But we were not on a raid like they were. It was during the wartime, when the Germans were occupying Norway.

“We were taking refugees across the Norwegian Sea to Shetland, often twenty of them at a time, hidden down below. Sometimes they were Jews escaping from the Nazis. Sometimes it was airmen who had been shot down, commandos we had been hiding, secret agents too. Fifteen times we went there and back and they didn’t catch us. Lucky, we were very lucky. This is a lucky boat. The other one, the one I built, was not so lucky. ”

Ragnar Erikson wasn’t the kind of man you could question or interrupt, but I was wondering all through our supper of herring and salmon, in the warmth of his kitchen that evening, what he had meant about the other boat. And I still hadn’t dared to broach the subject that puzzled me most: why there seemed to be no one else living in the village. When he fell silent I felt he wanted to be lost in his thoughts, and so the right moment never came. But after supper by the fire, he began to question me closely about why I had come sailing to Norway, about what I was doing with my life. He was easy to talk to because he seemed genuinely interested. So I found myself telling him everything: how at thirty-one I had found myself alone in the world, that my mother had died when I was a child, and just a couple of months ago my father had too. I was a schoolteacher, but not at all sure I wanted to go on being one.

“But why did you come here?” he asked me. “Why Norway?”

So I told him how, when I was a boy, I had been obsessed by the Vikings; I’d loved the epic stories of Beowulf and Grendel; I’d even learned to read the runes. It had become a lifelong ambition of mine to come to Norway one day. But arriving here in this particular fjord had been an accident – I was just looking for a good sheltered place to tie up for the night.

“I’m glad you came,” he said after a while. “As I said, no one comes here much these days. But they will, they will.”

“Who will?” I asked him, without thinking, and at once regretted it for I could see he was frowning at me, looking at me quite hard suddenly, and I feared I might have offended him.

“Whoever it is, they will be my family and my friends, that’s all I know,” he said. “They will live in the houses, where they all once lived, where their souls still live.”

I could hear from the tone of his voice that there was more to tell and that he might tell it, if I was patient and did not press him. So I kept quiet, and waited. I’m so pleased I did. When at last he began again he told me the whole story, about the empty village, about the other boat, the boat he talked about as if it had been cursed.

“I think perhaps you would like to know why I’m all alone in this place?” he said, looking directly at me. It felt as if he was having to screw up all his courage before he could go on.

“I should have gone to the wedding myself,” he said, “with everyone else in the village, but I did not want to. It was only in Flam, down the fjord just north of here, not that far. The thing was, that ever since I was a little boy, the bride had been my sweetheart, the love of my life, but I was always too timid to tell her. I looked for her every time I went to Flam to collect supplies, met her whenever I could, went swimming with her, picking berries, mountain climbing, but I never told her how I felt. Now she was marrying someone else. I didn’t want to be there, that’s all. So my father skippered my boat that day instead of me. There were fourteen people in the boat – everyone from the village except for me and two very old spinster sisters. They did everything together, those two. One of them was too sick to go, so the other insisted on staying behind to look after her. I watched the boat going off into the morning mists. I never saw it again, nor anyone on board.

“To this day, no one really knows what happened. But we do know that early in the evening, after the wedding was over, there was a rock-slide, a huge avalanche which swept down the mountainside into the fjord, and set up a great tidal wave. People from miles around heard it and saw it. No one saw the boat go down, but that’s what must have happened.

“For a few years the two old sisters and I kept the village going. When they died, within days of one another, I buried them in the churchyard. Then I was alone. To start with, very often, I thought of leaving, but someone had to tend the graves, had to ring the church bell, so I stayed. I fished, I kept a few sheep in those days. I had my horse. I learned how to be alone.

“I discovered there is one thing you have to do when you are alone, and that is to keep busy. So every day I work on the houses, opening windows in the summers to air rooms, lighting fires in the winters to warm them through, painting windows and doors, fixing where I can, just keeping them ready for the day they return. There’s always something. I know it’s looking more and more untidy as the years go by, but I do my best. I have to. They’re all living here still, all my family and friends. I can feel them all about me. They’re waiting, and I’m waiting, for the others to come and join them.”

“I don’t understand,” I told him.

“No, young man,” he said, laughing a little. “I’m not off my head, not quite. I know the dead cannot come back. But I do know their spirits live on, and I do know that one day, if I do not leave, if I keep ringing the bell, if I keep the houses dry, then people will find this place, will come and live here. In the villages nearby, they are still frightened of the place. They think it is cursed somehow. But they are wrong about that. It was the boat that was cursed, I tell them, not the village. Anyway, they do not come. Most of them are so frightened, they won’t even come to visit me. They say it is a dying village and will soon be a dead village. But it is not, and it will not be, not so long as I stay. One day people will come and then the village will be alive once more. I know this for sure.”

**

Ragnar Erikson offered me a bed in his house that night, but I said I was fine in the boat. I am ashamed to admit it but after hearing his story I just didn’t want to stay there any longer. It was too easy to believe that the place – paradise that it looked – might be cursed. He did not try to persuade me. I am sure he knew instinctively what I was feeling. I told him that I had to be up early in the morning, thinking I might not see him again. But he said he would be sure to see me off. And he was as good as his word. He was down on the quay at first light. We shook hands warmly, friends for less than a day, but I felt, because he had told me his story, that in a way we were friends for life. He told me to come back one day and see him again if ever I was passing. Although I said I would, I knew how unlikely it would be. But, through all the things that have happened to me since, I never forgot the saga of Ragnar Erikson. It was a story that I liked to tell often to my family, to my friends.

1st August 2010. Midnight.

Today I came back to Arnefjord. It has been over forty years and I’ve often dreamed about it, wondering what happened to Ragnar Erikson and his dying village. This time I have brought my family, my grandchildren too, because however often I tell them the story, they never quite seem to believe it.

I had my binoculars out at the mouth of the little fjord and saw the village at once. It was just as it had been. Even the boat was there at the quay, with no one on it, so far as I could see. There was no smoke rising from the chimneys; when we tied up, no one came to see us. I walked up towards the village shop, the grandchildren running off into the village, happy to be ashore, skipping about like goats, finding their land legs again.

Then, as I walked up towards the church, I saw a mother coming towards me with a pushchair.

“Do you live here?” I asked her.

“Yes,” she said, and pointed out her house, “over there.”

My granddaughter came running up to me.

“I knew it, Grandpa,” she cried, “I always knew it was just a story. Of course there are people living here. I’ve seen lots and lots of them.”

And she was right. There was a toy tractor outside the back door of a newly painted house, and I could hear the sound of shrieking children coming from further away down by the seashore.

“What story does she mean?” the mother asked me.

So I told her how I’d come here over forty years before and had met Ragnar Erikson, and how he was the only one living here then.

“Old Ragnar,” she said, smiling. “He’s up in the churchyard now.”

She must have seen the look on my face. “No, no,” she said, “I don’t mean that. He’s not dead. He’s doing the flowers. We wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for him. Ragnar saved this village, Ragnar and the road.”

“The road?” I asked.

Fifteen years ago they built a road to the village, and suddenly it was a place people could come to and live in. But there would have been no village if Ragnar hadn’t stayed, we all know that. There are sixteen of us living here – six families. He’s old now and does not hear so well, but he is strong enough to walk up the hill to ring the bell. It was the bell that brought us back, he says. And he still likes to go on ringing it every day. Habit, he says.”

I went up the hill with my granddaughter, who ran on ahead of me up the steps and into the church. When she came out there was an old man with her, and he was holding her hand.

“She has told me who you are,” he said. “But I would have recognised you anyway. I knew you would come back, you know. You must have heard me ringing. If I remember rightly, you liked ‘Whiter Shade of Pale’ on the Wurlitzer. And you liked a beer. Do you remember?”

“I remember,” I said. “I remember everything.”

Copyright © 2010 Michael Morpurgo. All rights reserved.

Supported through the Scottish Government’s Edinburgh Festivals Expo Fund.

- 2025 Festival:

- 9-24 August

Latest News

Communities Programme participants celebrate success of 2024

Communities Programme participants celebrate success of 2024