Paper Boat Paper Bird

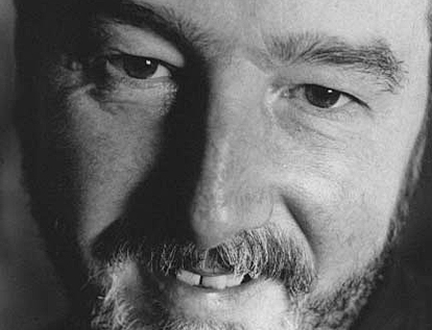

By David Almond

We have commissioned a new piece of writing from fifty leading authors on the theme of 'Elsewhere' - read on for David Almond's contribution.

Kyoto. Ky-o-to! Kyo-to! She feels so weirdly at home. She is herself, Mina, but it’s like there’s another Mina waiting to be discovered or created here.

“That’s travel,” says her mum. “Turns the world into somewhere else and turns you into someone else.”

This morning they’re off to the Golden Temple. They’re on a packed bus. Mina stands squashed in the aisle. Her mum’s at the front, watching for the temple stop. She keeps turning and peering through the bodies. Mina waves: don’t worry. Look! Here I am!

There’s a woman sitting on a seat beside her. The woman appears to be completely on her own. She’s calmly folding a square sheet of paper. She folds it edge to edge, point to point. She opens it, closes it, tugs and teases it into shape. Her lips move, as if she’s silently singing in time with the movement of her fingers. She swiftly makes a little boat. She holds it on her open palm and moves her hand gently back and forward, up and down. It’s like she’s on the bus but not on the bus. The boat moves as if it’s floating on a lake inside the bus that’s there for anyone to know.

She sees Mina watching. She smiles and bows her head.

“Konichiwa,” she says.

Mina smiles and bows her head as well.

“Konichiwa.”

She feels the strange neat movements of her lips and throat and tongue as they make the lovely word. She says it again to feel the word in her mouth and to hear the sharp sound of it.

“Ko-ni-chi-wa.”

The woman floats the boat towards Mina with her hands.

Go on, take it, she says with her eyes.

Mina takes it and rests it on her own palm.

“Arigato,” she says. “A-ri-ga-to.”

Float it, says the woman with her eyes.

Mina floats it through the tiny empty spaces around her body and the spaces open and the waters rise.

The woman laughs and claps her hands silently. She starts on another sheet of paper - folds it, creases it, tugs and teases it into shape. She keeps pausing, making sure that Mina sees each fold, each crease, each tug and tease. Look, she’s saying, this is how it’s done. Mina watches the woman’s fingers and the crowds around her disappear. Kyoto is gone. The bus is gone. She imagines what it would be like to be a sheet of paper in the woman’s hands, to be folded and creased and teased into shape, to become a paper Mina.

Maybe the woman knows this. She smiles deep into Mina’s eyes as if she knows everything.

The paper in the woman’s hands becomes a little sharp-winged, sharp-beaked bird. She holds it between her thumb and fingers and flies it through the spaces around her. She flies it towards Mina.

Take it, she says with her eyes. Fly it.

“Arigato,” says Mina.

She takes the bird. She can feel the vibrations of the woman’s fingers within it. With the bird flying between her fingers, she’s surrounded by empty air, by great stretches of water.

The bus sighs to a halt. The woman shrugs, smiles, stands up.

“Sayonara,” she says.

She hands Mina some sheets of paper.

“Sa-yo-na-ra,” says Mina. “A-ri-ga-to.”

The woman twists her way to the opening door and she steps out into the crowds.

Mina looks through her own reflection into the street outside. She sees the woman then loses sight of her then sees her again but the crowds close around her and the bus moves on and she’s gone.

Mina carefully folds the boat and the bird flat and puts them into her sketchbook with the sheets of paper.

The bus continues through the busy streets, through all the noise, past skyscrapers, hotels, flower sellers, flashing lights, cyclists, geishas, sushi shops, punks, cinemas, statues, tourist groups, burger bars, lanterns, pachinko parlours, shrines, road signs, lorries, buses, cars, crowds.

Mina sees how beautiful it all is. So much of it is recognisable, but so much of it is just so strange. The bus glides and sways. The bodies around her sway against her. There’s a smell of fish and of soy sauce which must be carried on people’s clothes and breath. The thrill of being here in Kyoto! She remembers roaring up into the clouds and leaving England behind. Then the oceans they crossed, the sky they flew through, the mountains and countries and cities below. Now home is on the earth’s far side and this is Japan. She saw it first at the crack of dawn from miles up in the sky. There it was, the country that seemed to float on the sea.

“Ja-pan,” she whispers. “Ky-o-to!”

She feels the little bursts of breath in her mouth. She thinks of the world turning and turning through endless space. She feels the great stretches of emptiness that are inside her.

“Mina!” calls her mum. “Mina, here we are!”

The bodies part, letting Mina through.

“Here I am,” she says.

They walk along the path towards the temple gardens.

“Keep close,” says her Mum. “Don’t get lost.”

Mina shows her lovely paper gifts.

She floats the boat and flies the bird.

They buy their tickets, which bear the name of the place then a picture of it, then unreadable and beautiful writing beneath.

The gravel gently rattles under their feet as they walk through the gates. There are rocks, pine trees, narrow pathways, stone lanterns, then the lake, then the golden temple, and beyond the temple there are trees, low hills then dark and distant mountains and the sky.

“The temple’s called Kinkaku-ji,” says her mum.

“Kin-ka-ku-ji,” says Mina.

“It contains the ashes of Buddha. It was burned down by a distressed monk in 1950 and was rebuilt again. It is considered to be the same place, even though it’s new.”

She sighs and laughs at the outrageous idea, at the outrageous beauty of the place.

“Maybe it suggests that nothing is ever truly lost, that everything will return.”

“Maybe,” says Mina.

She thinks of her lost dad for a few moments, as she does each day. He would have loved this place so much. Then she turns her mind back to the temple.

It is reflected in the lake. It appears to be floating on another temple. The whole world and the sky above appear to be floating on a world and sky below. Mina looks down into the lake, and another Mina looks back up at her.

“Konichiwa,” she whispers.

“Ko-ni-chi-wa,” mouths the other Mina.

Now her Mum looks back at her from the lake and waves. Mina sees how alike they are, how they are reflected in each other.

“Konichiwa,” they say.

Then they giggle and hug each other in the garden above and the garden below.

Mum goes wandering. Mina sits on a rock by the lake and watches the visitors. A man and boy crouch close by her and peer down into the water as if they’re passionately searching for something. Many people do the same, of course, as if the glassy water pulls them to it. When the man and boy stand up, the boy pretends that he’s about to dive in. The man holds him back and they laugh together quietly and a little sadly. Then they walk on.

She catches the boy’s eye as he passes by.

“Konichiwa,” she whispers, but he’s lost in thought.

Mina draws a picture of the temple. She speaks its name, Kinkaku-ji, as she draws, and she writes the name too, so that the image, the word, the sound and its movements are all the same thing.

She writes a tiny note about what happened in the bus:

The packed Kyoto bus. A paper-folding woman. Birds fly from her hands.

She takes a piece of the woman’s paper and writes a message on it.

My name is Mina. Whoever finds this will be my friend forever.

She folds the paper edge to edge, point to point. She makes a boat with it. Nowhere near as good as the woman’s boat, but something the same. She takes another sheet of paper and folds that, too.

On this she simply writes, Mina.

She makes a bird with it, again nowhere near as good but still it’s a bird.

She looks at the world, blinks, and looks again. She imagines a whole world made of folded paper: paper temple, paper trees, paper rocks, paper people, all neatly folded and creased in a paper world. She smiles at the lovely illusion.

Then she puts the bird into the boat and stands up.

There are streams flowing through the garden. She kneels beside one of them and carefully places the boat into it and lets it go.

“Sayonara,” she whispers as the boat and the bird are carried away through the rocks and the pine trees. “Sa-yo-na-ra,” until they’ve completely gone from sight.

Then her mum’s voice:

“Mina! Where are you?”

Mina hurries back to the lake. She waves.

“I’m here!” she calls.

“I’m here,” she calls silently from the world below.

That evening they eat sushi and sashimi and flakes of something that’s hardly there at all except for the intensity of the taste it leaves on the tongue. They walk home through the crowds, past the blazing lights of bars and department stores. They’re staying in a little timber house in a narrow street near the centre of the town. It’s a place with small sparse rooms, low lights, pale gliding shutters, tatami mats on the floors. There’s a bathroom with a deep stone bath and with openings in the wall where steam gushes out and a machine for making powdered ice.

In Mina’s room a little stone Buddha sits in a shrine with sprigs of cherry blossom and an incense burner. Mina lights the incense and scented smoke drifts through the room. She puts her bird and her boat on the shrine. She lies on a futon on the floor. Her Mum’s singing in the room next door. The city drones beyond the walls. The moon shines in through the window. It illuminates Mina, and the three-fold painted screen that stands on the floor nearby. Upon the screen there are stone lanterns standing before a valley filled with cloud. There are distant jagged mountains. Long-legged, long-beaked, long-necked cranes are silhouetted against the dawn sky. They appear to be flying through this world towards another or into this world from another.

When she sleeps, she dreams of the bird and the boat that have been carried away, She dreams of being the paper-folding woman. She folds and creases and tugs and teases. She holds her creations in her open hands: look, this is how it’s done. Deep into her dreams she makes a dark-haired, dark-eyed boy.

The boy smiles.

Mina smiles back at him.

“Konichiwa,” she says.

Her lips and tongue and breath form the sharp neat shapes and sounds.

“Ko-ni-chi-wa.”

And then she falls into the deep dark silent lake that surrounds us all.

Early next morning, at the edge of Kyoto, the boy is swimming in Biwa Lake. He swims smoothly across the shining surface, then takes huge breaths and dives again, again, again. He loves moving in the depths, with the light above and the darkness below and the silvery flashes of fish around him. He loves to burst out into the air, to curve, to dive down deep again.

This morning there isn’t much time. His father’s already called him.

“Miyako! Miyako!”

He climbs out onto the bank and crouches at the edge. He bangs two sticks together.

Crack! Crack! Crack!

Black and silver fish rise and gather at the sound.

Crack! Crack! Crack!

“Konichiwa,” he whispers.

He drops crumbs towards their mouths that silently open and close, open and close.

“O O O,” say the fish in silence. “O O O.”

“Sayonara,” says Miyako.

He’s turning away when a little paper boat appears, floating on the surface. He leans down and lifts it out. There’s a paper bird inside it.

“Miyako!” calls his father. “We have to go!”

He stands and sees his father on the narrow beach beside their towels.

“Where are you, Miyako?”

“Look! I’m here, Dad!”

He hurries to him. He dries himself and puts his clothes on. They get into a car, and head into Kyoto.

Miyako inspects the boat and the bird as they travel.

His dad glances at them.

“Origami,” he says. “And not very good.”

“And very wet,” says Miyako, as the boat collapses between his fingers. He opens it and finds the blotchy faded words inside. He learns English at school, but most of this has seeped into the paper and is pretty meaningless. All he can decipher are the letters that make ‘name’, ‘Mina’ and ‘ever’.

He finds the message in the bird as well.

“Mina again,” he says.

He refolds the bird and flies it through the tiny spaces around him.

“Careful,” says his dad. “Don’t block my view.”

The streets are packed, the roads are so busy, the traffic’s so slow. Dad keeps looking at his watch.

“We’ll be late,” he says. “She’ll think we’ve forgotten about her.”

“Hardly!” says Miyako.

He thinks of the one who wrote the messages. English, maybe. And probably a girl. He flies the bird before his eyes, and it’s as if he can still feel the vibrations of its maker within it. He thinks of the girl, and an image of her starts to appear in his mind.

They don’t really know it, of course, but as they get close to the centre of Kyoto they slowly pass Mina and her Mum, who are standing at a tiny temple that’s squashed in between a shoe shop and a bank. They’ve just rung a bell that hangs from the temple eaves. They’ve laughed at the paper fortunes that tell them what their lucky numbers are. Mina throws a coin into a small stone pond of golden fish. Miyako watches her. There’s something familiar in the way she moves, the way she bows her head. He continues to fly the bird. Mina suddenly turns and sees the boy flying a bird inside a car.

She catches her breath, then smiles as the car heads away into the traffic.

“Everybody makes them,” she says.

Soon Miyako’s dad drives underground, into a huge downward-spiralling car park. They’re down at level 6 before they find a space. Then they hurry to the escalators that zigzag through a huge department store towards the sky.

Sakura’s at a table in the open roof café. She has a pot of coffee with two cups, and a glass of lemonade. She stands when she sees them, bows and smiles. Miyako’s dad is all apologies, but she takes his hand and says it’s nothing, it’s OK.

“Good morning, Miyako,” she says. “You have been in the water today?”

“Yes,” he says.

She indicates the lemonade.

“For you,” she says.

He thanks her. They’re still awkward with each other. Miyako plays with the bird as she and his dad talk and laugh about some mysterious theatre they saw together.

Miyako unfolds the bird and writes his name beside the name of Mina. He makes the bird again, then slips away from the table and goes to the parapet. He looks back. Sakura’s OK, he supposes. His dad’s laughing again. Change is coming, he knows that.

Miyako looks down over beautiful Kyoto: the crowded streets, the skyscrapers, the flashing lights, the gardens. He sees Kinkaku-ji itself. He’s even sure he can see its reflection in the water.

He holds the bird above the parapet and flicks his wrist and lets it fly.

Mina and her Mum walk happily arm-in-arm. Mina’s imagining, as she often does, that her dad is walking beside her, too. Mum’s bought a print of Mount Fuji rising from the mist. Mina’s bought some manga, two versions of the same story contained within one book. The English version starts from the left, the Japanese from the right. The versions end and come together at the centre.

Mina and her mum love the crowds, the shops, the buses, the food, the temples. They love the silence and stillness at the heart of it all. It’s the last day. Tomorrow it’s a bullet train to Hiroshima. But they feel that even when they’ve left this place they’ll still be here.

Mina looks up as they walk and here’s the bird, swaying, falling, spinning, flying, a single tiny bird in all that space, a single tiny bird in space that goes on forever, as far as distant England, as far as the furthest star.

Mina raises her hands and the points of the bird touch the points of her fingers. She neatly folds her hands around it, then opens them, and shows it resting there.

“It can’t be,” says her Mum.

But it is. Mina opens the bird, and there’s her name, with the new unreadable beautiful word by its side.

They look up into the emptiness. There’s nothing they can say.

They walk on through indecipherable Kyoto.

Miyako and his dad and Sakura come down on the zigzag escalators. Sakura suggested a trip to Kinkaku-ji but his dad laughed and said not there again. So they’re heading for MacDonald’s and the cinema. Miyako knows they’re doing it for him. That’s OK. He’s starting to feel at ease with her. He’s even starting to like her, and to feel happy for his dad.

They walk through the sea of people. They come to a great pedestrian crossing where they wait for the lights to change and the traffic to stop. Mina and her mum are waiting at the far side.

The moment comes and the tides of people flow towards each other in the crowded city beneath the empty sky.

Mina and Miyako see each other.

They stop, and bring the adults who are with them to a stop as well.

“Konichiwa!” says Miyako.

“Ko-ni-chi-wa!” says Mina.

Copyright © 2010, David Almond. All rights reserved.

Supported through the Scottish Government’s Edinburgh Festivals Expo Fund.

Look, Listen & Read

- 2025 Festival:

- 9-24 August

Latest News

Communities Programme participants celebrate success of 2024

Communities Programme participants celebrate success of 2024