Red Wolves in the Mist

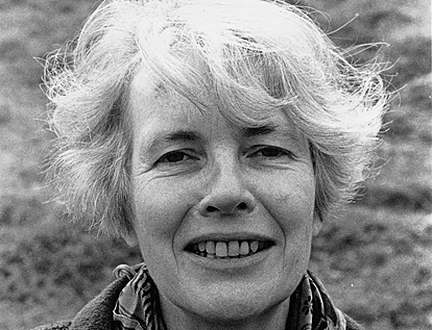

By Elizabeth Laird

We have commissioned a new piece of writing from fifty leading authors on the theme of 'Elsewhere' - read on for Elizabeth Laird's contribution.

The wolf came towards us out of the mist, trotting on stilted legs. He was lean but his black-tipped tail was bushy. Unlike his grey European cousins, he was rust-red, bright enough to stand out vividly against the chalky green vegetation.

I'd cursed the cloud which had rolled down upon us as we'd driven up through the belt of juniper and eucalyptus forest which ringed the lower slopes of this high plateau in Ethiopia's Bale Mountain region. But the mist had begun to clear enough for our eyes to follow the wolf's jerky progress across the tree-less ground. He turned and looked at our Land Rover, weaving his head from side to side as if to focus his eyes. His snout was long. He opened his mouth to yawn and his slim tongue curled back into his mouth. Then he trotted on.

"He is a juvenile," my companion, Tsegaye, said. "His coat is not so red yet."

We abandoned the car and set off on foot across the spongy ground, which was pitted with the burrows of mole rats, the wolves' chief source of food. I struggled to fill my lungs in the thin air and shivered in the biting wind. An eagle circled above us, calling mournfully. There was no other sound, except for the crunch of our feet on the tiny Afro-Alpine flowers, blue, yellow, white and purple, and the crackle of Tsegaye's cheap nylon anorak. I had never before been wrapped in such a silence.

We took shelter from the wind behind a cow-sized boulder. It was spattered with lichens: stiff, yellow-grey, coral-like growths, flat rosettes of burning orange and clumps of green moss. They looked like splashes of paint. Scrapings in the earth behind the rock showed where a wolf had begun to hollow out a den.

The mist was lifting properly now and some way below us, on the track where we had left the Land Rover, a caravan of pack ponies had appeared. The small chestnut horses wore crimson saddlecloths and were laden with white sacks of grain. They seemed out of place in this moon-like landscape.

"They are merchants," said Tsegaye. "That is the highest road in Africa."

He pulled the collar of his anorak higher round his neck. His head was shaved up the sides to leave a mop of black curls on top. His skin was the warm red-brown of the Ethiopian highlander.

A dog ran behind the pack ponies. Tsegaye shook his head at the sight of it. The dog looked innocent enough but it represented a threat, I knew. There are fewer than five hundred of Ethiopia's red wolves in the entire world. They are scattered about in the highest mountain regions, small populations separated from each other by vast stretches of lowland. There are none in captivity. As the population of Ethiopia surges, shepherds seeking new pastures drive their flocks ever higher towards the fragile mountain tops, bringing their dogs with them. It is the dog-borne infections of rabies and distemper which principally threaten the wolves. An epidemic can wipe out a significant proportion of their entire number in a season.

There is no great animosity between villagers and wolves.

"The farmers appreciate the cleverness of the wolf to hunt the mole rats," Tsegaye told me. "They do not take lambs from them, as jackals do."

Not a curl of mist now remained and I could see the sweep of the plateau rising to even higher mountains beyond. Giant lobelias, palm-like plants, stood above the woody shrubs like single sentinels.

As we walked back to the Land Rover, mole rats bounced away from us, the fur on their fat brown rumps fluffed against the cold.

We saw three more wolves that morning. I bragged of this to Dr Karen Laurenson, one of the vets working on the wolf conservation project, when, shaking drops of moisture from our hair, we arrived back at the research station.

The scientists' house was a long building with a covered veranda on a steep hillside. Inside the fieldwork room, maps and charts were pinned to the bare wooden walls, and a table was littered with lab equipment, old notebooks, abstracts of theses, a tilly lamp and a vase of scarlet flowers.

The scientists running the project were dauntingly energetic. Enduring the cold, the monotony, the lack of comfort and the simplest diet, they were focussed entirely on the wolves. Here in the research station was evidence of the work: the education programme in the surrounding villages, charts recording dog inoculations, the birth of wolf pups and incidences of disease.

"Good luck today," Karen announced, as we sat around in the glow of a lamp over a meal of spaghetti. "Eve's found a dead horse."

"Well, it was dying so I hastened its end." Eve Pleydell, blond and pretty, was delicately winding spaghetti round her fork. "I thought it would come in handy."

"Do you want to come out with us tonight?" Karen asked me. "We're going to use the horse as bait and see if we can dart some hyenas. We need to know if they're a reservoir for rabies and canine distemper, like the dogs. We'll have a go at testing them for antibodies."

We found the horse conveniently positioned on a grazing place where hyenas often came at night, not far from a small town. The pick-up bumped over the rough ground until its headlamps lit the dark lump of the dead creature lying on the ground. A small group of people were clustered round it. Eve had set a man to guard it, and others had come out to see what was going on.

Tsegaye and Idris, another worker on the project, shone their torches on the corpse. It was a horrible sight, its belly already swollen, its old sores scabrous, its hide patchy with mange, its tongue falling out, its dead protruding eye white and glazed. Karen and Eve picked up a hind leg each and flipped the thing over.

"Anyone got a machete?" Karen asked. "We'd better chop off some pieces."

Eve produced her penknife, slit the skin by the hip joint and stuck her fingers into the bloody mess. The watching men, wrapped up against the biting cold in their shroud-like white shawls, made loud remarks which, perhaps fortunately, neither young woman could understand.

"Okay. Let's pull the leg off now," said Eve, grabbing it and twisting it round. There was a sound of tearing flesh and she staggered back with the leg in her hands. Karen had fished out the horse's liver and baited it with anaesthetic. She now stuffed it back into the horse's body.

"Idris, could you ask these people to go away?" she said. "Any minute now, they're going to be surrounded by hyenas."

There should have been a full moon but clouds were covering the sky. From the small town I could hear the thump, thump of a generator. Dogs barked and a lorry revved its engine.

I helped Eve to set a loudspeaker on the roof while Karen loaded the fearsome-looking dart-gun. Only a few flickers of light from the houses in the town pierced the darkness. I could see a faint outline of hills, rising and dipping on the horizon against a pale edging of sky which was lit dimly by the moon behind the clouds.

Karen and Eve worked steadily, preparing their equipment, head torches strapped on. It was the first time they had tried doing this, and they had planned it meticulously.

"If we get a hyena down, we're doing the measuring and the whole works, right?" Eve asked Karen.

"Yes."

The loudspeakers were now ready on the roof.

"I'll just load up two darts," said Karen, pushing a syringe into the anaesthetic phial. "Idris, did you ask those guys? It's getting a bit crowded round here."

Idris clearly knew the men well and was a skilled go-between. He talked to them quietly, answering questions, keeping his body language respectful, and after some laughter and murmurs of agreement his good manners worked and the onlookers moved off into the darkness.

"Get in the back of the car," said Karen to me. "If you're outside the hyenas won't come anywhere near."

She backed the pick-up away, leaned the dart-gun on the open window, and pointed it towards the dead horse. Eve sat beside her. I was squashed between Idris and Tsegaye, grateful not only for the warmth of their bodies, as it was now very cold, but also for their reassuring bulk which separated me from the darkness outside, which now felt full of menace. Eve flicked a switch on the tape recorder connected to the loudspeaker on the roof and the air was filled with the bellow of an animal in the extremity of suffering.

"A dying wildebeest. I got it from the Serengeti," Karen said.

And now, over this unearthly, gut-wrenching wail, I could hear the whooping calls of hyenas. I tried to suppress my shudder, not wanting to betray myself to the men beside me.

The moon came out. I could make out the shape of the dead horse but nothing else.

"Hey! What's that?" said Eve.

"Damn! A dog. The hyenas'll keep away if there are dogs around."

Idris bravely got out of the pick-up and made rushes at the dog, trying to scare it, but it dodged past him, grabbed the baited liver out of the horse's body and ran off.

"It'll take him a while to sleep that off," said Karen. "Must be another dead horse somewhere around. By now you'd have expected a dozen hyenas, right in close. We'll have to move Dobbin further out of town."

She reversed the pick-up back towards the horse and Eve tied the tow-rope round one of its remaining legs. We bumped away across the grazing land on which the grass had been shaved by cows' teeth down to a thin velvet, with the ghastly remains of the horse bouncing along behind us, and stopped again to begin another long wait.

The moon was fully out now. We sat in silence in the Land Rover hearing nothing but the groaning of the wildebeest from the roof and the occasional shriek of a nightbird. I felt the presence of the mangled horse, its throat cut, waiting for the final horror to begin. Straining our ears, we heard at last the derisive howls of hyenas from close by. They were circling us and we could sense their nervousness and doubt. They were too far away to shoot at.

"They're scared," Karen said at last. "They don't like the car and the smell of people. Let's give it up for tonight."

"I'll take another leg off the horse," said Eve. "We can always find a use for it."

I couldn't help feeling relieved. I had been safely cocooned between two beefy Ethiopians in the back of a large vehicle. There had been no danger to me, but a primitive horror had made my hair stand on end. I had some small inkling of what it must be like to live in a flimsy house, the walls made of nothing stouter than flimsy sticks or matting with a door of simple wooden planks, while outside in the dark powerful creatures prowl, waiting for a chance to tear me to pieces.

It's ten years now since I watched the wolves on their mountain tops and saw the conservation team at work. Since then, not much has changed. Rabies has struck again, twice, but the wolves have clung on, bringing themselves back once more from the brink and producing sturdy litters year by year.

I wrote a novel for children about the wolves of Ethiopia. It was called Red Wolf, and soon went out of print. But I think often of those lean, elegant creatures and the brave people trying to hold at bay the dangers that threaten to overwhelm them. From the heat and hassle of London, their cold, remote world seems unbearably beautiful: a precious, fragile place. The wolves pass their days as they always have done, pursuing their plump little victims, courting each other, giving birth and caring for their young. Tiny bright flowers are their carpet. Swirling clouds hide and then reveal them.

We are all implicated in the wolves' plight. In a feeble shake of my fist at the forces of planetary destruction, I plant up my garden with vegetables and put out my newspapers to be recycled. Nothing I do will be enough.

I want the wolves to survive. I want their world to survive.

To find more about the Ethiopian wolf, check out the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme at www.ethiopianwolf.org

Look, Listen & Read

- 2025 Festival:

- 9-24 August

Latest News

Communities Programme participants celebrate success of 2024

Communities Programme participants celebrate success of 2024