Once upon a time

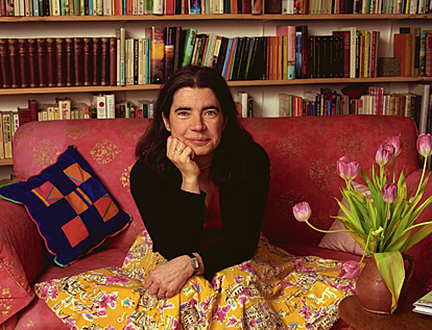

By Debi Gliori

We have commissioned a new piece of writing from fifty leading authors on the theme of 'Elsewhere' - read on for Debi Gliori's contribution.

Stories? The importance of books? Don’t get me started. The harder life gets, the more the need to escape. Stories offer a way out, an alternative world-view, an elsewhere that is not here and not now. Just like a drug.

Read enough of them and you’ll put up with a lifetime of hell because deep down you’ll be convinced that it’ll all end happily ever after. Or you’ll spend your life in the company of frogs because, thanks to stories, you’ll believe that hidden under that amphibian skin is the beating heart of a true prince. Or you’ll buy into the myth that if you’re good and truthful and kind, when you die you’ll go to heaven.

Oh, please. The only truth is that nobody gets out alive. Nobody.

I wasn’t always like this. Back then, Air used to complain that Mac and I would believe anything as long as it came from a book. But now Air’s dead, and Mac – well, Mac is elsewhere. He’s so very elsewhere, nobody can reach him.

It all began, as so much did back then, with a book. To understand, you’d have to go back in time to primary school, to primary five, when Mac arrived halfway through the winter term. He was the new boy, parachuted into a class struggling with maths, English and rolling strike action that was threatening to close the school indefinitely. Mac appeared in our midst, all freckles and sticky-out joints; red-haired, bespectacled and, at first sight, one of those children sporting a sign that read ‘born victim’. The Neanderthals in our class lit up at the sight of fresh meat but, to our surprise, within a few days of his arrival, Mac had everyone eating out of his hand. Mac, we all agreed, had the gift of the gab. Mordantly funny and utterly self-deprecating, everyone wanted Mac to be their friend. However, to my astonishment, Mac singled me out for the role of sole keeper-of-secrets and brother in arms. Within days we were inseparable, spending every spare moment in each other’s company, sharing our deepest, secret thoughts, hopes and fears until one of us only had to think about something before the other gave it voice.

In an age before mobiles and laptops, books were our common ground. I’d always had my nose firmly buried in some story or other, and in Mac I found myself not only mirrored but magnified tenfold. Where I read, Mac devoured. I absorbed and quoted from what I discovered between the pages, but Mac ate, breathed, lived and became the stories. For Mac, the border between reality and fiction didn’t exist. Or to put it another way, from the moment he could read, he’d had his head halfway down the rabbit-hole listening for the ticking of a tardy rabbit’s watch. For Mac, every stand of trees was a Wild Wood, every wardrobe offered passage into another world and, if he overturned enough boulders, one day he’d be sure to find a Psammead.

As we moved from primary to high school, Mac’s belief in the world of the imagination barely changed. Externally, adolescence was wreaking its usual havoc; spots, gangly limbs and crashing silences interspersed with the honks, squeaks and vocal uncertainties of puberty. But internally, Mac remained utterly true to his essential ‘Mac-ness’. He was old-young, wise beyond his years and, despite being the weediest boy in our year, he attracted a disproportionate share of adoring and adorable young women. Playing Wendy to his Peter, Air attached herself to Mac and thus became part of my life too.

Like musketeers, we drew strength from our threesome. Air was tough, sassy and streetwise. She tolerated Mac’s and my love of fiction, but preferred hers in the form of newspapers.

‘You’re havering,’ she’d mutter, faced with one of Mac’s more outlandish fantasies.

‘Get a grip, guys,’ she’d insist when Mac and I scared ourselves witless with some horror story we’d ramped up to fever pitch by our over-taxed imaginations. But in the end, all her common sense failed to save her. Air was undone by friendship; loyalty proved to be a more lethal weak spot for fortune’s arrows than any ancient Greek’s dodgy heel.

I said it began with a book, but in truth it began with Mac’s big sister Mhairi. As we went into second year at high school, Mhairi had been about to do her final year in medicine at Glasgow University. There was an incident with a drunken driver on Great Western Road. Mhairi, cycling back from the library with her panniers crammed full of textbooks, didn’t stand a chance. Death had been instantaneous.

On such tragic happenstances, entire lives spin out of orbit. Coming back to school a week after the funeral, Mac was visibly altered. We gathered round him, Air and I, trying to heal him with kindness, but we couldn’t reach him. Months went by, the year turned, but Mac still failed to show any signs of recovery.

I suspect the accidental nature of his sister’s death preyed on his mind; the ‘what ifs’ and ‘if onlys’ keeping him awake and angrily grieving. He refused to talk about it. His eyes were permanently red-rimmed and, if a stick insect could be said to have lost weight, Mac looked physically diminished.

‘Can’t even escape into a book right now,’ he confessed. ‘It’s too much effort and, besides, none of the characters seem to make sense any more. Their hopes and dreams are just ... pointless. I find myself losing interest round page fifty...’

‘Try short stories,’ Air suggested. ‘Most of them aren’t any longer than fifty pages.’

‘I loathe short stories,’ Mac said. ‘Not even sure we’ve got any at home.’

But he did. The next week he was telling us what an amazing writer H.G. Wells was. The week after that, there was a light in his eyes that I hadn’t seen since the accident. After the first anniversary of Mhairi’s death, Air and I began to think the worst was over. And thus, we picked up the weft of our friendship and carried on, Mac’s sister buried, his grief apparently absorbed and our whole bright future ahead of us. Or so we thought.

Winter came in hard and fast that year, the jobless total crossed the three million mark, oil prices went through the roof, the stock market plummeted and a mood of bleak hopelessness seemed to engulf the nation. Mac, Air and I drew closer together, trying to keep the shadows at bay. We reasoned that this was an adult mess not of our making and, being teenagers, we tuned it out, turned up the volume of our music and assumed that if our parents’ generation hadn’t totally destroyed the planet by the time we inherited it, we’d soon sort it all out.

That night, we were holed up in Mac’s bedroom, but it could just as easily have been mine, or Air’s. Even now, I still find myself wondering if we might have prevented what happened. It’s as if by changing one simple thing, Mac and Air’s story could have had a different ending. However, in this story, Air was reading the newspaper out loud, while I riffled through Mac’s collection of vinyl and Mac did headstands against the bedroom door.

‘The more I read of this crap, the less I want to grow up,’ Air said, crumpling the paper into a ball and hurling it into a corner of the room. Mac, toes tapping out a rhythm on the door, ignored her completely and whistled tunelessly under his breath.

‘Don’t you think? Mac? Mac?’ Air persisted.

‘I do think,’ Mac said, eyes still closed. ‘Actually, I think a lot. I spend a lot of time upside down as well. It improves the flow of blood to my brain and therefore sharpens my ability to think, or so Mhairi says.’

Air’s head spun round and she locked eyes with me. ‘Says?’ she mouthed, with an imperceptible jerk of her head in Mac’s direction. Her expression at this point was mildly perplexed. Later it was to become confused, aghast and ultimately, blank. But for now, she was bemused. As was I. Perhaps ‘Mhairi says’ was only a slip of the tense. Perhaps Mac had meant to say, ‘Mhairi said’ or ‘Mhairi used to say’. A slip, I decided, just as Mac’s eyes opened and he curled up and dropped his feet to the floor, accidentally knocking half a mug of lukewarm coffee across Air and I before turning himself right way up.

‘Actually,’ he continued, as we mopped up the spillage, ‘I’ve been thinking a lot recently,’ and something in his eyes made me think – WHOAH, hang on – but then he was off, verbally sprinting miles ahead, each sentence tumbling out in a chaotic jumble of pseudo-science, hippy mystical shite and a slew of freaky syntactical connections that left my head spinning. Beside me, Air’s head shook rapidly from side to side in a palsy of denial.

‘Wait. Wait. Aw, come on, Mac. You know that’s not poss – just calm it, would you?’ she begged. But Mac, now started, proved to be unstoppable.

‘I know. You think I’m crazy, but you don’t know, you can’t know till you’ve tried it. It’s ... incredible. Mhairi knows, she’ll convince you. Mock all you like but once you see it … I’m telling you, it works. IT WORKS!’

It?

‘It’ being, for want of a better term, a time machine. That’s time machine as in a device that allows the user to wilfully flout the laws of physics and enter the realm of pure science fiction. This had to be a joke. Mac was winding us up, big-time. Actually, as a wind-up, it was too good. Mac was too convincingly mad. In truth, he was scaring the living daylights out of me and, judging by Air’s expression, she wasn’t far behind. Enough, already. I tried for levity, and failed.

‘Mac, for God’s sake. You can barely make your own bed. Toast is a task too far. How the hell d’you expect us to believe you could possibly make a time machine?’

No answer, just a glittering smile and a shrug. Across from me, Air dug her fingers into her hair and hung on for dear life as if her head was threatening to blow off.

‘Aw, come on. Mac ... pal ... I know Mhairi’s death blew you apart, but this is crazy. Mhairi is dead. She isn’t ... You can’t ...’

‘She’s not dead,’ Mac insisted. ‘At least, not in the past, she’s not. Don’t you see? I can go back. I can be with her before the accident. I can talk to her. Ask her stuff. She showed me how to make it work. Look, I’ll prove it to you. Come with me. I’ll show you.’ He grabbed Air’s arm, his face twisted with effort, desperately searching for the words that would make us believe him. ‘You can help. I want to find out what comes next. In the future. To see if we can make things better.’

With hindsight, that was the point at which I should have found Mac’s parents and begged them to get help for their rapidly unravelling son. But that would have meant telling Mac that what he was describing was impossible and that we thought he was losing it. How could we, his friends, be the ones to destroy the entire fragile, tottering edifice he’d constructed to cope with the grief of losing his sister? One of the most terrifying aspects of that night was the extent to which Mac had somehow, without our noticing it, become completely reliant on fantasy. He must’ve spent months building an internal Mac-logic to explain how such an impossibility could work. Many years later, I learned that psychologists have a phrase for this – cognitive dissonance. It is, in essence, doing something with one half of your mind while you force the other half to look away. It is a splitting of one’s person that, depending on the depth of the schism, can become a permanent feature.

As we followed Mac downstairs, with him babbling maniacally about time tourism and the wonders of the future ahead, I felt hollowed-out by fear but still hoped that somehow, miraculously, he was telling the truth. Then we were outside, Air and I still coffee-stained and damply shivering in the chill wind. We followed Mac down the path, past abandoned flower-beds, and into the garden shed.

Before Mhairi’s death, Mac’s Dad had made some attempt at keeping the garden in check, but the subsequent fifteen months of neglect had taken their toll. Mac flung the door wide to reveal rakes and hoes rusting on their hooks. Seeds spilled out of rotting packets and bird shit speckled the floor. In a corner, shrouded by hessian sacks, lay Mac’s invention. If further evidence was needed of Mac’s slipping grasp on reality, the jumbled mess in front of us was proof positive that our friend was ill and had been for some time. I saw a car seat complete with seat belt, a vintage vacuum cleaner, a dry-cleaner’s bag draped over a standard lamp and a clock radio gaffer taped to the top of a computer monitor. And all around, a fankle of jump leads, cables and extension leads, all wired, taped and spliced together with no regard for compatibility or purpose.

Air turned aside, hiding her face from view, and I avoided making eye contact with Mac but, by then, he was so intent on demonstrating the effectiveness of his machine that I doubt he noticed.

‘I know, I know,’ he muttered, flicking switches and, to my horror, plugging something into a wall socket. ‘Doesn’t look like much, but just you wait till we get this baby up and running, then you’ll see...’

Oh, I saw all right. I saw something I’ll never forget, no matter how hard I try. Mac slid into the car seat, solemnly belted himself in, pulled the plastic dry-cleaner’s bag over his head and fired up the vacuum cleaner. What the hell he thought he was doing I have no idea but, as the plastic instantly moulded itself to his face, Air leapt forwards yelling, ‘NO! NO! Idiot – you’ll suffoc-’

There was a blue flash, Air gave a sort of surprised half-cough, half-grunt, and then she flew backwards and crashed to the floor. She landed on one of Mac’s tangles of wiring and, what with her recent dousing in cold coffee and the time I took to realise that she was actually being electrocuted and wasn’t simply kicking the floor in pain and fury, she was well and truly dead.

Let’s skip ahead several chapters to where Mac sits on his bed by the window. There’s not much of a view, but he stares out at the courtyard where fellow travellers walk aimlessly, round and round and back and forth, smoking as if their lives depended on it. At first, I wasn’t allowed to see him for fear I’d remind him of the night I lost them both. Then things relaxed a bit, and I’d cycle up after school on Fridays and make my way to the ward to see my friend. After Mac’s parents died I became his sole visitor, apart from the odd aunt or social worker who’d grown attached to him over the years. So many years, now.

Air is firmly fixed in time; forever thirteen – a child compared to Mac’s and my middle-age. We’re the adults now, and according to the news we’re still making a mess of everything. But here, Mac has the advantage. Grey and balding, Mac can time travel at will. He calls up Mhairi and Air and, judging by Mac’s roars of laughter, they all appear to have a great time together. He doesn’t need a time machine to go back any more. In a rare moment of clarity after some cock-up with his medication, he told me he’d downloaded a time travel app straight onto his internal hard drive which allowed him to move freely through time and space.

Which is, all things considered, just as well. Look closely and you’ll see that Mac’s bed has long restraining straps sewn onto the mattress. The windows in his room don’t open. Occasionally, when Mhairi and Air whoop it up a bit too much, Mac ends up face-down on the floor with the duty doctor giving him an extra shot of something to bring poor Mac slamming straight back into the present, time travel apps notwithstanding.

The truth is that Mac’s story will not end with a happy ever after. Although I cannot see them, I know that Mac believes Mhairi and Air are beside his bed. They watch and wait, Mhairi’s arm round the younger girl’s shoulders, comforting her, telling her some lie or other that she read, all those years ago, in one of the books she used to carry home from the university library.

‘Once they find the correct medication, my brother will be able to lead a normal life.’

Poor Mhairi; her books say this, so it must be true.

Air leans down and pats Mac’s arm and whispers, ‘And when you die, you’ll go to heaven.’

She is dead, so you’d imagine she’d know better than to spout this nonsense, but billions of books agree so it must be true. They removed the bible from Mac’s room after he tried to eat it, page by page, but I imagine he could still recite whole chunks if he so desired. He doesn’t, thankfully. Instead, he looks out of the window, at the walking lost, at the stranded time travellers smoking in the courtyard, at the dust motes caught in sunlight, at a moth struggling to free itself from a long-abandoned web.

Copyright © 2010 Debi Gliori. All rights reserved.

Supported through the Scottish Government’s Edinburgh Festivals Expo Fund.

Look, Listen & Read

- 2025 Festival:

- 9-24 August

Latest News

Communities Programme participants celebrate success of 2024

Communities Programme participants celebrate success of 2024